Following the demise of the Bangor Abby, the Scot-Irish remained passionate about their primary Presbyterian faith. Their continued quest for freedom lead to many conflicts including their support of King William III who offered some measure of independence apart from the Church of England. Keep in mind that the Church of England was formed by King Henry VIII because the Catholic Church refused to grant him an annulment to a marriage that failed to produce a male air to his throne. When the Pope refused, Henry VIII decided to form his own church so that he could find another wife.

Presbyterian history is part of the history of Christianity, but the beginning of Presbyterianism as a distinct movement occurred during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. As the Catholic Church resisted the reformers, the Church split and different theological movements bore different denominations.

Presbyterianism was especially influenced by the French theologian John Calvin, who is credited with the development of Reformed theology, and the work of John Knox, a Scotsman who studied with Calvin in Geneva, Switzerland and brought his teachings back to Scotland. The Presbyterian church traces its ancestry back primarily to England and Scotland. In August 1560 the Parliament of Scotland adopted the Scots Confession as the creed of the Scottish Kingdom. In December 1560, the First Book of Discipline was published, outlining important doctrinal issues but also establishing regulations for church government, including the creation of ten ecclesiastical districts with appointed superintendents which later became known as presbyteries. In time, the Scots Confession would be supplanted by the Westminster Confession of Faith, and the Larger and Shorter Catechisms, which were formulated by the Westminster Assembly between 1643 and 1649.

The Massacre

The Scottish Reformation was Scotland's formal break with the Papacy in 1560, and the events surrounding this. It was part of the wider European Protestant Reformation; and in Scotland's case culminated ecclesiastically in the re-establishment of the church along Reformed lines, and politically in the triumph of English influence over that of the Kingdom of France.

The Reformation Parliament of 1560, which repudiated the pope's authority, forbade the celebration of the Mass and approved a Confession of Faith, was made possible by a revolution against French hegemony. Prior to that, Scotland was under the regime of the regent Mary of Guise, who had governed in the name of her absent daughter Mary, Queen of Scots (then also Queen (consort) of France). The Scottish Reformation decisively shaped the Church of Scotland and, through it, all other Presbyterian churches worldwide.

The evangelical revival in Scotland was a series of religious movements in Scotland from the eighteenth century, with periodic revivals into the twentieth century. It began in the later 1730s as congregations experienced intense "awakenings" of enthusiasm, renewed commitment and rapid expansion. This was first seen at Easter Ross in the Highlands in 1739 and most famously in the Cambuslang Wark near Glasgow in 1742. Most of the new converts were relatively young and from the lower groups in society. Unlike awakenings elsewhere, the early revival in Scotland did not give rise to a major religious movement, but mainly benefited the secession churches, who had broken away from the Church of Scotland. In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century the revival entered a second wave, known in the US as the Second Great Awakening. In Scotland this was reflected in events like the Kilsyth Revival in 1839. The early revival mainly spread in the Central Belt, but it became active in the Highlands and Islands, peaking towards the middle of the nineteenth century. Scotland gained many of the organisations associated with the revival in England, including Sunday Schools, mission schools, ragged schools, Bible societies and improvement classes.

The Cambuslang Work, or ‘Wark’ in the Scots language, (February to November 1742) was a period of extraordinary religious activity, in Cambuslang, Scotland. The event peaked in August 1742 when a crowd of some 30,000 gathered in the ‘preaching braes’ - a natural amphitheatre next to the Kirk at Cambuslang - to hear the great preacher George Whitefield call them to repentance and conversion to Christ. It was intimately connected with the similar remarkable revivalist events taking place throughout Great Britain and its American Colonies in New England, where it is known as The First Great Awakening.

The Holy Fair was a biennial rural celebration of the Communion once common in Scotland, attended not only by the people of the parish, but by large numbers of strangers from far and near. Their acts were of questionable decency, however, and were exposed and satirised by the poet Robert Burns in his poem The Holy Fair.

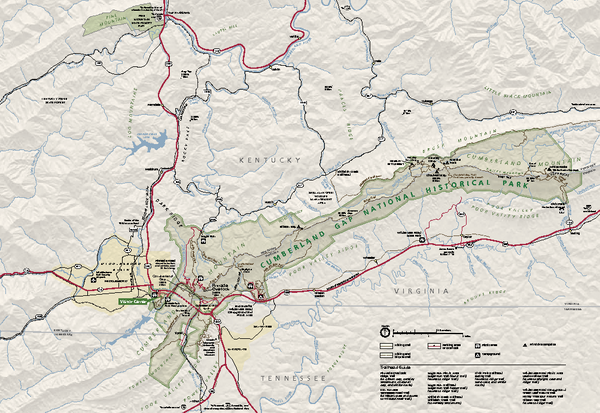

With the mass migration to the colonies some 200,000 Scot-Irish brought their passionate faith with them to the frontier. With the west opening to settlement, many Scot-Irish made their westward journey through what is now known as Cumberland Gap into central Kentucky and Middle Tennessee. At Cumberland Gap, the first great gateway to the west, follow the buffalo, the Native American, the longhunter, the pioneer... all traveled this route through the mountains into the wilderness of Kentucky.

The passage created by Cumberland Gap was well-traveled by Native Americans long before the arrival of European-American settlers. The earliest written account of Cumberland Gap dates to the 1670s and was written by Abraham Wood of Virginia.The gap was named for Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, son of King George II of England, who had many places named for him in the American colonies after the Battle of Culloden. The explorer Thomas Walker gave the name to the Cumberland River in 1750, and the name soon spread to many other features in the region, such as the Cumberland Gap. In 1769 Joseph Martin built a fort nearby at present-day Rose Hill, Virginia, on behalf of Dr. Walker's land claimants. But Martin and his men were chased out of the area by Native Americans, and Martin himself did not return until 1775.

In 1775 Daniel Boone, hired by the Transylvania Company, arrived in the region leading a company of men to widen the path through the gap to make settlement of Kentucky and Tennessee easier (See reference to the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals in Part 1 of this series) . On his arrival Boone discovered that Martin had beaten him to Powell Valley, where Martin and his men were clearing land for their own settlement – the westernmost settlement in English colonial America at the time. By the 1790s the trail that Boone and his men built was widened to accommodate wagon traffic and sometimes became known as the Wilderness Road.

Since the American Revolution, Christianity had been on the decline, especially on the frontier. Sporadic, scattered revivals—in Virginia in 1787–88, for example—dotted the landscape, but they were short-lived. Religious indifference seemed to be spreading.

On a trip to Tennessee in 1794, Methodist bishop Francis Asbury wrote anxiously about frontier settlers, “When I reflect that not one in a hundred came here to get religion, but rather to get plenty of good land, I think it will be well if some or many do not eventually lose their souls.”

Andrew Fulton, a Presbyterian missionary from Scotland, discovered in Nashville and in “all the newly formed towns in this western colony, there are few religious people.” The minutes of the frontier Transylvania Presbytery reveal deep concern about the “prevalence of vice & infidelity, the great apparent declension of true vital religion in too many places.”

Rampant alcoholism and avaricious land-grabbing were matched by the increasing popularity of both universalism (the doctrine that all will be saved) and deism (the belief that God is uninvolved in the world). Methodist James Smith, traveling near Lexington in the autumn of 1795 feared that “the universalists, joining with the Deists, had given Christianity a deadly stab hereabouts.”

During the six years preceding 1800, the Methodist Church—most popular among the expanding middle and lower classes—declined in national membership from 67,643 to 61,351. In the 1790s the population of frontier Kentucky tripled, but the already meager Methodist membership decreased.

Churches and pastors did not merely wring their hands; they clasped them in prayer—at prayer meetings, at worship, and at national conventions. In 1798 the Presbyterian General Assembly asked that a day be set aside for fasting, humiliation, and prayer to redeem the frontier from “Egyptian darkness (obvious reference to a well known fraternal order still active today).”

With the westward migration of the Scot-Irish into the interior of America, the stage was set for yet another God encounter with the passionate Presbyterians. All it took for this short but intense outpouring was the announcement of a outdoor communion service. Having lived through generational religious repression, the Scot-Irish responded by opening the door in what is now known as the Second Great Awakening in the United States.

The Cane Ridge Revival was a large camp meeting that was held in Cane Ridge, Kentucky from August 6 to August 12 or 13, 1801. It has been described as the "largest and most famous camp meeting of the Second Great Awakening." This camp meeting was, in fact, that which many contend to be the pioneering event in the history of frontier camp meetings in America. It was based at the Cane Ridge Meeting House and drew between 10,000 and 20,000 people. According to The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement, logistical considerations make it unlikely that more than 10,000 could have been present at any one time, but 20,000 could have attended the meeting at some time during the week, which would have been "nearly 10 percent of the recorded population of Kentucky in 1800". At least one, and possibly more, speaking platforms were constructed outside the building because the number of attendees far exceeded the capacity of the meeting house.

The meeting was hosted by the Presbyterian church at Cane Ridge and its minister, Barton W. Stone. The church decided to invite other local Presbyterian and Methodist churches to participate in its annual Communion service. Ministers from Presbyterian, Methodist and Baptist backgrounds participated. Eighteen Presbyterian ministers participated, as well as numerous Methodists and Baptists, but the event was based on Scottish traditions of Holy Fairs or communion seasons.

The meeting began on a Friday evening with preaching continuing through Saturday, and the observation of communion beginning on Sunday. Traditional elements included the "large number of ministers, the action sermon, the tables, the tent, the successive servings" of communion, all part of the evangelical Presbyterian tradition and "communion season" known in Scotland. An estimated 800 to 1,100 received communion. During the meeting multiple ministers would preach at the same time in different locations within the camp area, some using stumps, wagons and fallen trees as makeshift platforms.

Friday, August 6, 1801—wagons and carriages bounced along narrow Kentucky roads, kicking up dust and excitement as hundreds of men, women, and children pressed toward Cane Ridge, a church about 20 miles east of Lexington. They hungered to partake in what everyone felt was sure to be an extraordinary “Communion.”

By Saturday, things were extraordinary, and the news electrified this most populous region of the state; people poured in by the thousands. One traveler wrote a Baltimore friend that he was on his way to the “greatest meeting of its kind ever known” and that “religion has got to such a height here that people attend from a great distance; on this occasion I doubt not but there will be 10,000 people.”

He underestimated, but his miscalculation is understandable. Communions (annual three-to-five-day meetings climaxed with the Lord’s Supper) gathered people in the dozens, maybe the hundreds. At this Cane Ridge Communion, though, sometimes 20,000 people swirled about the grounds—watching, praying, preaching, weeping, groaning, falling. Though some stood at the edges and mocked, most left marveling at the wondrous hand of God.

The Cane Ridge Communion quickly became one of the best-reported events in American history, and according to Vanderbilt historian Paul Conkin, “arguably … the most important religious gathering in all of American history.” It ignited the explosion of evangelical religion, which soon reached into nearly every corner of American life. For decades the prayer of camp meetings and revivals across the land was “Lord, make it like Cane Ridge.”

What was it about Cane Ridge that gripped the imagination? Exactly what happened there in the first summer of the new century? The key to understanding the nature of Cain Ridge and its historic influences on religion in America clearly lies in understand the culture and passion of the Scot-Irish. A seed was planted in a people group that is still growing in a Nation that it gave birth to. Passion for God never found a more fruitful heart! Bravo, well done my Scot-Irish friends!

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.